The Spiez laboratory: a quiet success story

4 March 2018 – A man and woman are found unconscious in Salisbury, England. After a while it becomes clear who they are: Sergei Viktorovich Skripal and his daughter Yulia. Why is this significant? Because Skripal was a colonel in the Soviet and then Russian military intelligence, the GRU, who defected and became an informant for the British secret service MI6. Soon enough, it transpires that both father and daughter are the victims of an attempted poisoning. The world's press gets its hands on a story worthy of James Bond. And the Spiez lab gets a job... But what is this laboratory exactly?

Set in Switzerland – acting for the world

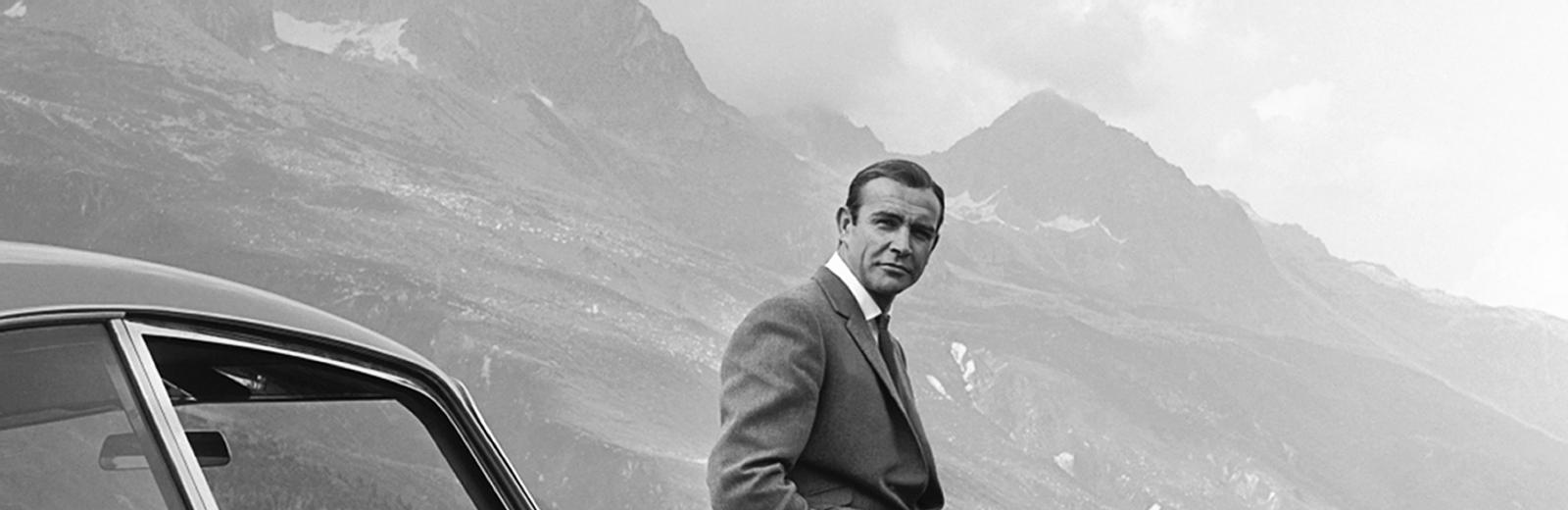

Even James Bond author Ian Fleming guessed that this small country in the heart of Europe is capable of great things, or he wouldn't have chosen a Swiss woman, Vaud-born mountaineer Monique Bond née Delacroix, to be the mother of the world's most infamous secret agent. But just as the reader only learns about Bond's mother's identity in passing, so is it with the story behind the Spiez laboratory.

Everyone knows that it exists, but even the lab itself reveals nothing about its work. Just like the motto 'do good and (don't) talk about it'. If Bond had grown up in his mother's native country and started working for the Swiss Federal Intelligence Service, he may well have come into contact with the Spiez lab.

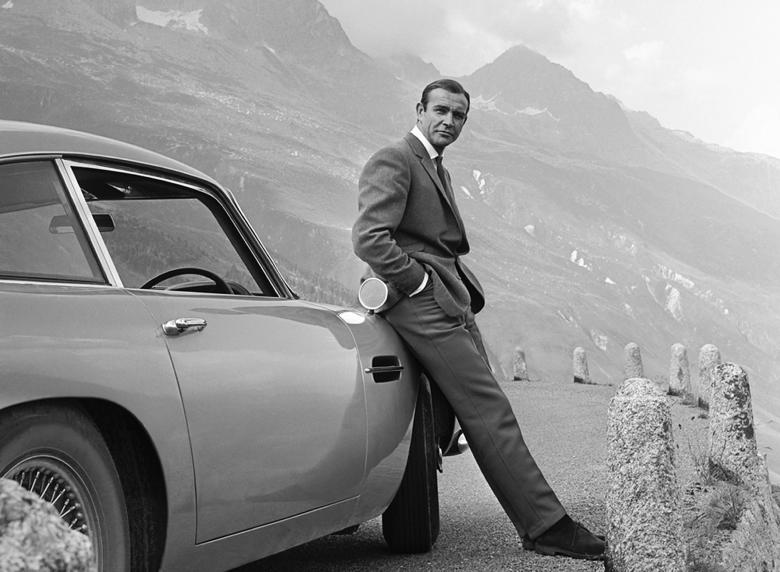

But given the fact that His Majesty's secret service provided him with an Aston Martin for work, you can understand why Bond, aka 007, would rather work for MI6. It is still entirely possible that the agent came into contact with the laboratory during his career – not that we would be able to find out, given their level of discretion – because it wasn't just one time that Bond was sent to Switzerland. There was the time he crossed the country in his Aston Martin DB5, chasing gold smuggler Auric Goldfinger in the 1964 film of the same name over the Furka Pass in a 1937 Rolls-Royce Phantom III equipped with golden chassis. Or the time in the 1969 On Her Majesty's Secret Service when he hunted down arch-enemy and head of the criminal organisation SPECTRE Ernst Stavro Blofeld on the Schilthorn in the Bernese Oberland.

As is often the case with James Bond, both of these missions involved secret and highly dangerous substances – Goldfinger is about a gold substance that can suffocate a person if it comes into contact with their skin; On Her Majesty's Secret Service deals with a pathogen that could wreak disaster on the whole world. And we can assume that the Spiez laboratory would also have lent its discrete assistance in both of these cases. Why? Because analysing substances is one of their main activities. But what led the Swiss government to create this institute in the first place – an institute that doesn't just analyse substances any more, and no longer works exclusively for Switzerland but on behalf of the entire world?

Lessons from the First World War – how the Spiez lab was born

After poison gas had been used to devastating effect in the First World War (1914–18), the Swiss government felt obliged to act. In 1923 it approved a new section for gas protection at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH), which was relocated in 1925 to the Eidgenössische Pulverfabrik (now known as Nitrochemie) in Wimmis in the canton of Bern. This laid the foundation for the Spiez laborary – Switzerland's institute specialising in protection from atomic, biological and chemical hazards and threats.

The lab's initial focus was on developing gas masks. It also experimented with masks for cavalry horses after 1928. Military carrier pigeons were also to be protected, and the lab developed a model of a ventilated vehicle for carrier pigeons.

The Second World War

With the horrors of the First World War just behind them and those of the Second World War looming ahead, the Swiss government decided in 1937 at the request of the General Staff to make provisions for chemical warfare in the army. The chemicals industry, which is mainly located in Basel even to this day, produced a tonne of mustard gas in September 1939 at the request of the military department. On 29 September 1939, the government approved the production of 300 tonnes of the gas. A chemical warfare factory was also founded although it was never put into operation. After the Second World War, poison gas stockpiles were gradually dismantled from 1947 on. The last three tonnes were destroyed in the Spiez laboratory's chemical safety lab in the mid-1980s.

The postwar period

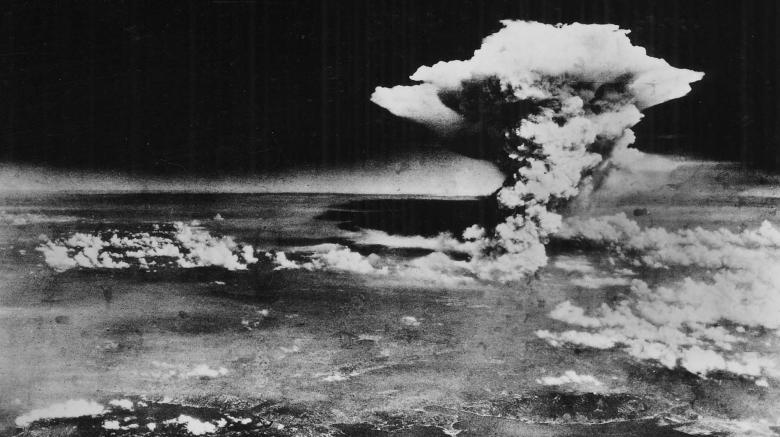

When atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, Switzerland was confronted by a weapon with an unprecedented capacity for destruction. To pool available resources, the Swiss authorities transferred testing for protective materials and devices to the Spiez laboratory, which was now in charge of dealing with this new threat. This additional field of activity culminated in the new name AC laboratory. The NBC (nuclear, biological, chemical) protection section at the Spiez lab continues to undertake quality inspections for shelters and protected premises, and the physics section works on issues dealing with the production, application, processing and destruction of nuclear weapons. Since the nuclear disasters in Chernobyl and Fukushima, civilian hazards related to nuclear technology have also been instrumental in shaping the laboratory's work.

Global orientation after the fall of the Berlin Wall

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the end of the Cold War, the Spiez laboratory underwent intense discussions about reorientation – based on the fact that comprehensive protection from NBC weapons included arms control measures in this area. Already in 1984, the UN secretary-general tasked a laboratory delegation to verify whether chemical weapons had been used in the war between Iraq and Iran (1980–88). Samples were tested in Spiez and, in the interests of obtaining a second independent opinion, in a laboratory in Sweden. Both found overwhelming evidence of mustard gas and tabun, a nerve agent.

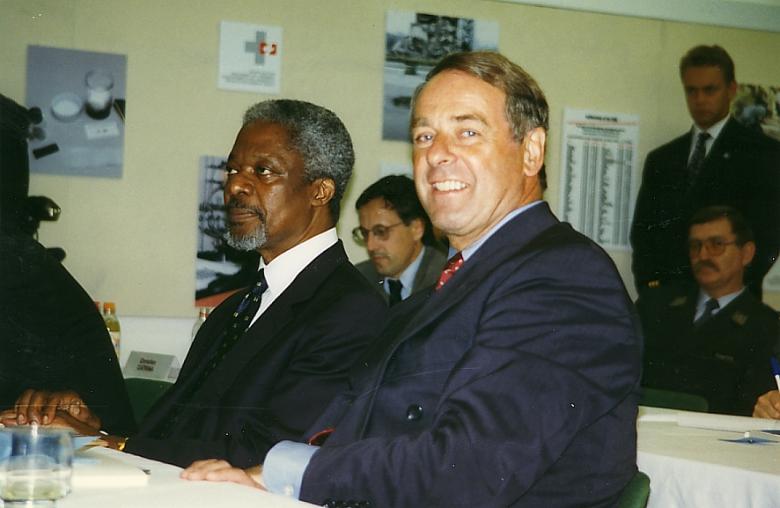

Other activities followed from this first mission in Iraq including the UN special commission to monitor the ceasefire agreement in Iraq, which was created in 1991 after the Second Gulf War. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan (1938–2018) praised the work of the Spiez laboratory, paying tribute to the institution during a personal visit in 1997.

In line with its new strategic orientation and Switzerland's diplomatic good offices, the Spiez laboratory began to provide expertise on a regular basis for Swiss delegations involved in disarmament talks. The lab also contributes to preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction by organising international conferences, which it continues to this day given the increasing significance of cooperation in terms of disarmament and peacebuilding. Over the decades, the Spiez laboratory has grown into a globally recognised centre of excellence and a veritable instrument of Switzerland's security policy. It should come as no surprise that the lab is among the 20 or so specialist laboratories worldwide that have been certified by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) since its establishment in 1997. Within this select group, the Spiez laboratory is among the very few to have fulfilled the OPCW's demanding requirements every year without exception – which is why it continues to serve as the OPCW's laboratory to this day. Against this backdrop and in view of the fact that since 1953 Swiss soldiers have been monitoring the ceasefire agreement between North and South Korea along the demarcation line in Panmunjom in what is the Swiss army's longest mission abroad, you can also see why, after US President Donald Trump's meeting with North Korean ruler Kim Jong Un in Singapore on 12 June 2018, the Spiez laboratory was already being touted by the media as part of the monitoring commission for a potential disarmament in North Korea.

Based as it is in a neutral country, the Spiez lab has become a key partner for the UN, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The importance of the lab's work can also be gauged by the fact that it is the trusted laboratory of three Nobel Prize winning organisations:

- 1963: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

- 2005: International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

- 2013: Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

And the Skripal case? The world's press, politicians, high-ranking officials and some self-appointed experts have been outdoing each another over the past few months with their conjectures, opinions and suspicions regarding the case, accusing one another of lying. Only the Spiez laboratory in the Bernese Oberland, tasked by the OPCW with analysing the poisonous substance, went about its work quietly, delivered its results and refrained from making any public statements. Even James Bond never made a fuss about all the times he saved the world.