8 Swiss inventions that changed the world

How did a burr end up in space? And what does a spilled glass of wine have in common with your sandwich wrap? The invention of the Velcro fastener and cellophane showcase a truly Swiss talent: converting crazy ideas into practical tools with catchy names. These are just two examples of Swiss ingenuity. Chemists and scientists from all walks of life have used their Swiss pragmatism over and over again to turn out inventions that have changed the world forever.

The zip – Martin Winterhalter (1925)

The Americans might have had the idea, but the Swiss perfected what we know today as the zip fastening. The original ‘pre-zip’ was patented in the US in 1851. It required two corresponding rows of hooks to be lined up in order for them to be fastened with a pull. Hardly the easy on/easy off zip that we know and love...

Enter a lawyer from St. Gallen. In 1923, Martin Winterhalter was approached by an American who held the patent on the latest version of the ‘pre-zip’. Winterhalter saw room for improvement, zippily investing 10,000 francs to acquire the patent.

By 1925, he had perfected the technology and the ‘coil zip’ was born – the interlocking tooth design that is still in use today. Another legend tells how Winterhalter protected his machinery in Germany and Luxembourg from the Nazis by smuggling it into Switzerland...

Velcro® – Georges de Mestral (1941)

You could say that the Swiss like things to stick. Does it surprise you that Velcro® was invented, patented and registered in Switzerland?

Hunting in the Jura mountains, a Swiss engineer noticed that certain seeds were attaching themselves to his clothes, as well as to his dog –and they were nigh on impossible to remove. On closer inspection, these ‘burrs’ seemed to have tiny hooks, attaching them tightly to fibres and hair.

© kalyanvarma, via Wikimedia Commons

With help from friends in the weaving industry, Georges de Mestral managed to replicate this ‘hook and loop’ fastening method in an invention. He named it velcro, from the French velour and crochet (velvet and hook). Although he marketed it as a ‘zipperless zipper’ in the 1950s, it took an organization like NASA to finally hook the world: in 1969, astronauts used Velcro® to secure things inside the Apollo spaceship.

Now, it may take another Swiss to quieten the loud noise that Velcro® makes – as well as to track down the name of the dog that inspired de Mestral.

The Rex vegetable peeler – Alfred Neweczerzal (1947)

The Rex vegetable peeler was invented and patented by Alfred Neweczerzal in 1947. Thanks to copycats, it is widely known as the ‘Y peeler’.

While one story goes that he came up with the gadget after becoming fed up peeling potato after potato in the military, his design definitely revolutionized kitchens across the world. Crafted from a single piece of aluminum, the original Rex was fast to produce, cheap to buy yet of high quality – and easy to use for left-handers and right-handers alike.

Another legend goes that a family asked Alfred’s grandson to replace the original Rex’s non-replaceable blade after sixty years of service! To this day, his grandson continues to produce to the same pattern, but in stainless steel or burnished carbon steel. And this Swiss peeler remains the sharpest.

Nescafé – Max Morgenthaler (1936)

In 1929, Brazil ended up with a large surplus of coffee beans as a result of the Wall Street crash. The Brazilian Coffee Institute subsequently approached Swiss firm Nestlé with a mission to save the Brazilian coffee farming industry by creating instant coffee with a delicious taste.

At the time, some form of instant, brown-coloured, caffeinated water was available, but it was missing that critical coffee flavour. After five years of failed attempts at preserving the true coffee taste in the form of powder, Nestlé pulled the plug on the experiment.

However, a staff chemist secretly kept trying different methods in his own time and at his own expense in his own kitchen near Vevey, Switzerland. In 1936, Max Morgenthaler presented a winning formula to Nestlé. The launch of Nescafé followed on 1 April 1938.

The bobsleigh track – Caspar Badrutt (1870)

‘Eins, zwei, drei…’ Anyone who has seen the 1993 film Cool Runnings knows that the Swiss are the team to beat in the bobsleigh, but they didn’t actually invent the sport. That came courtesy of British tourists in the late 19th century.

They were enticed by enterprising hotel owner Caspar Badrutt to try out his spa town of St. Moritz in the winter months. Perplexed at how to occupy themselves in the fledgling winter resort, they adapted delivery boys’ sleds and whizzed about the snow-covered streets.

However, it was the entrepreneurial Badrutt who turned the activity into a proper sport. He built a special run – the world's first natural ice half-pipe track – which hosted the first formal competitions in 1884. Still in operation, the track has hosted two Winter Olympic Games – and countless fast and furious tourists.

© Flyout (taken by ancestor of Flyout) [GFDL ], via Wikimedia Commons

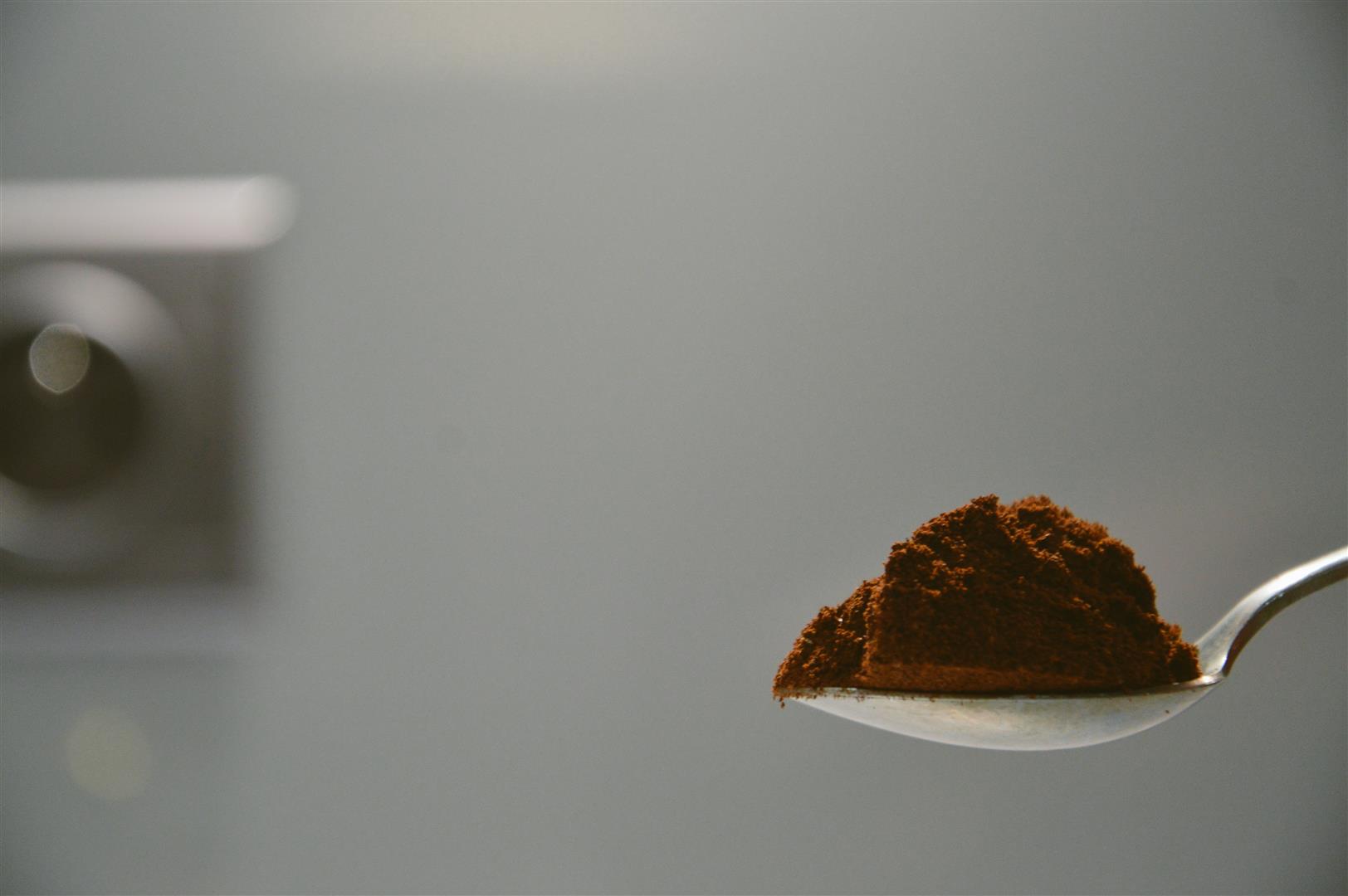

The World Wide Web – Tim Berners-Lee at CERN (1989)

The combination of British ideas and Swiss practicality seems to be a winner. Just over 100 years after the bobsleigh track, another English man was using the resources available in Geneva to create the World Wide Web.

It was while he was working at CERN that Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in 1989. Inspired by CERN’s own shared network, but frustrated that each computer stored information with a different login, Berners-Lee created his own version. The first website in the world was based at CERN, on Berners-Lee’s own computer, hosting information about how the web worked.

This “NeXT” machine – the original web server – is still at CERN today. In 1993, CERN released the software into the public domain, the World Wide Web was born, and the way we find, browse and share information changed forever.

© Max Braun via Visualhunt / CC BY-SA

Doodle scheduling – Michael Näf and Paul E. Sevinç (2007)

There is no such thing as being fashionably late in Switzerland. In a country where trains run to the second, and five minutes late is too late, scheduling is an art.

It should come as no surprise that digital scheduling was invented by a time-poor, idea-rich Swiss computer scientist and an electrical engineer – Michael Näf and Paul E. Sevinç. Frustrated at the complexity and inefficiency of a long e-mail chain to organise a get-together with friends, Näf came up with the concept of Doodle. This online platform allows invitees to mark their availability on a simplified shared calendar – a service now used by 20 million people each month.

Cellophane – Jacques E. Brandenberger (1912)

And to wrap things up…cellophane! A good glass of wine can often be called upon to get the creative juices flowing, but for Swiss chemist Jacques E. Brandenberger, it was the wine pouring out of the glass that sparked the imagination.

Inspired by seeing wine spill onto a tablecloth, he decided to invent a material that could repel liquids rather than absorb them. He started by spraying waterproof coating onto fabrics, but they became stiff and unusable, and the clear coating peeled off.

Cue Brandenberger’s next idea – seeing how easily the clear, waterproof coating separated from the fabric, he decided to explore the possibilities of this new substance. He dedicated the next 12 years to perfecting its construction and consistency, and manufactured a machine to produce the film. He named it cellophane, from cellulose and diaphane (French for transparent), and gave us a brand new, hygienic way of sealing leftovers for tomorrow.