The Swiss beginnings of LSD

In a stroke of serendipity 80 years ago, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann (1906–2008) discovered the effects of lysergic acid diethylamide – otherwise known as LSD. Initially this new hallucinogen was explored by Western scientists for its therapeutic potential. But LSD soon found its way out of the lab and into the world of recreational use by the counterculture movement. From the late 1960s it started to be banned, putting a halt to medical research in psychedelic substances. Since the 1990s, however, clinical studies of LSD have gradually resumed in some countries, including Switzerland.

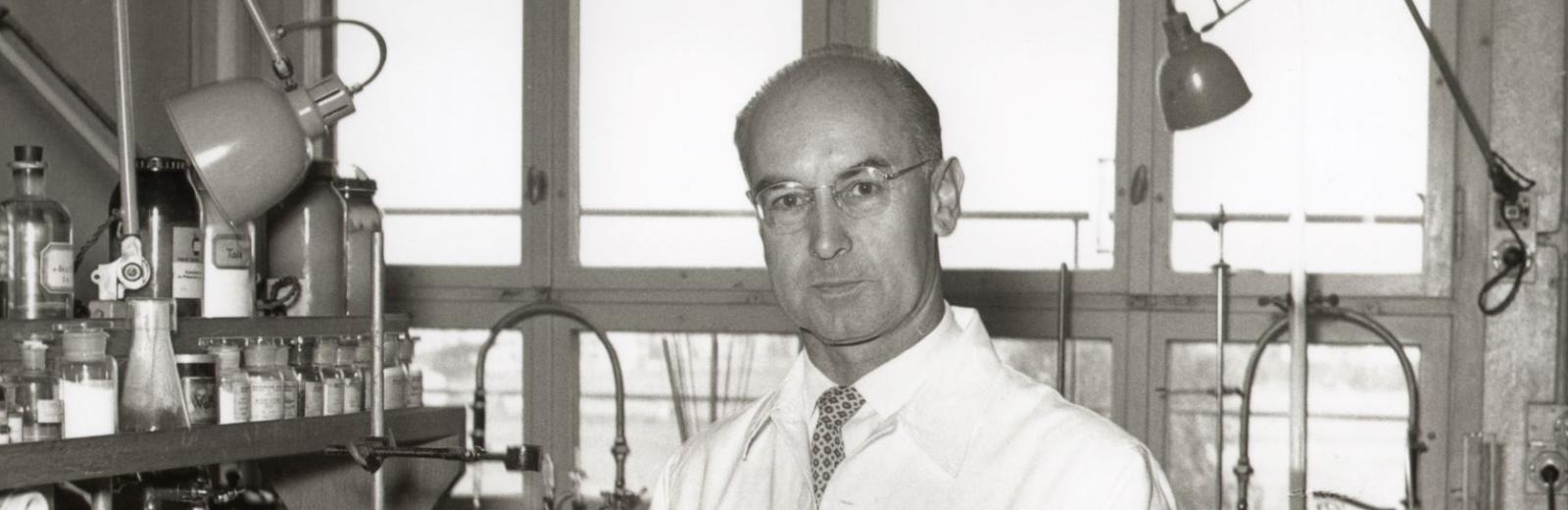

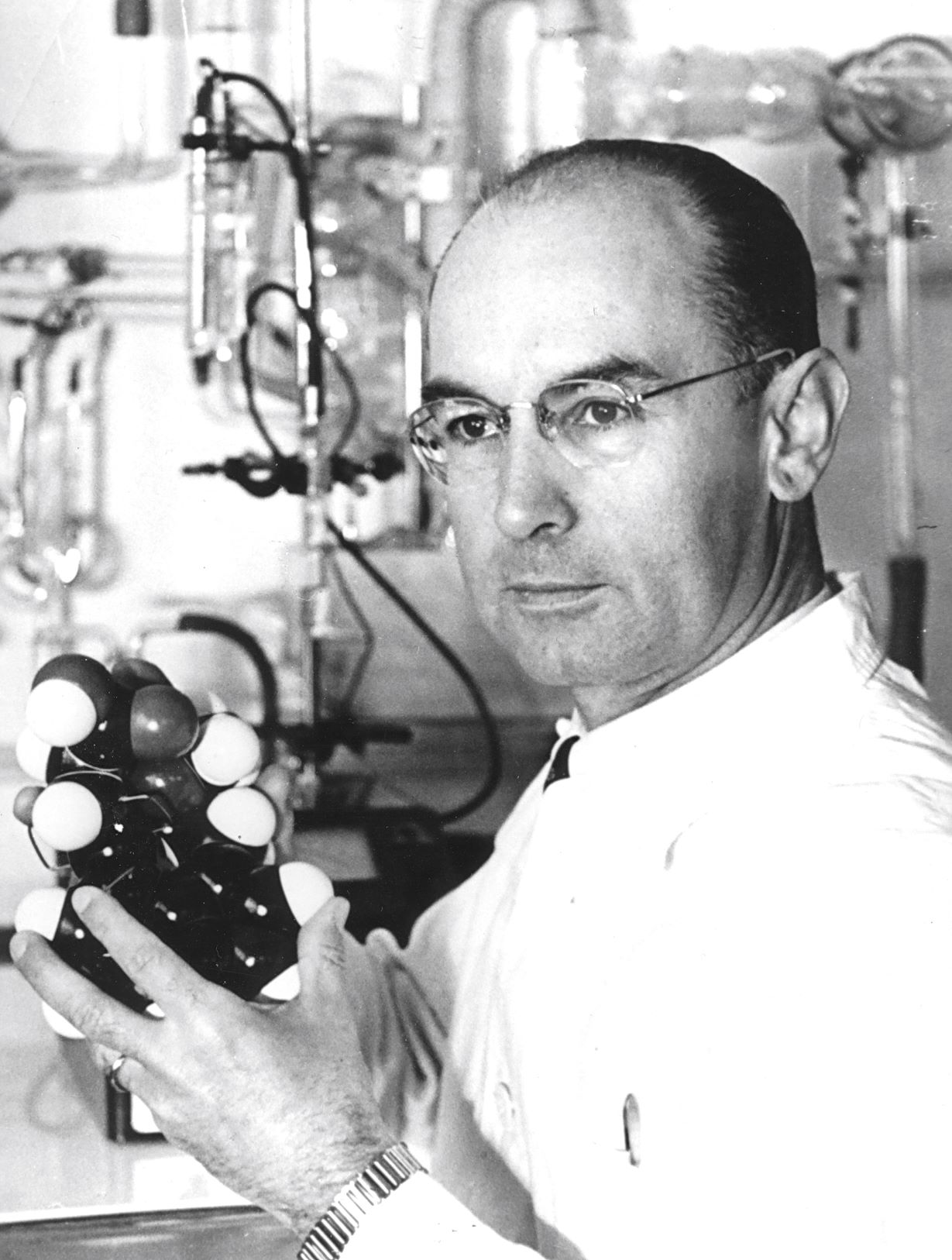

In his 1980 autobiography* Albert Hofmann described the first time he intentionally took LSD, on 19 April 1943. As a research chemist at Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, he ingested some of the substance he had synthesised in the lab, unaware of its effects. He then decided to cycle home, embarking on what turned out to be the first 'bad trip' in the history of LSD. But his experience paved the way for further scientific and psychedelic research.

A chance discovery

Albert Hofmann was born in Baden in 1906. After graduating from the University of Zurich with a chemistry degree, he joined pharmaceutical firm Sandoz in Basel. In 1938 he was working on a new circulatory stimulant and analysing the various components of ergot, a parasitic fungus that grows on rye. This was when Hofmann first isolated lysergic acid diethylamide. However, the new compound did not immediately show much potential and so he set it aside for a few years. When he returned to it in April 1943, he inadvertently absorbed a trace of the substance, probably by rubbing his eyes. But the strange sensations he felt intrigued him and he decided to run more tests.

A few days later, unaware of the potency of LSD and its hallucinogenic effects, Hofmann took what he thought was a tiny amount, 0.25 milligrams; in fact, this was a massive dose. After cycling home, it was as if he had found a way to a parallel universe. When his friendly neighbour dropped by, he saw her as a "malevolent, insidious witch with a coloured mask" and was unable to counter his altered perception of reality. "Every exertion of my will, every attempt to put an end to the disintegration of the outer world and the dissolution of my ego, seemed to be a wasted effort," he wrote in his autobiography. The effects finally wore off and Hofmann was more or less back to normal the following day.

"I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant to escort me home. On the way home, my condition began to assume threatening forms. Everything in my field of vision wavered and was distorted as if seen in a fun-house mirror. I also had the sensation of being unable to move from the spot. Nevertheless, my assistant later told me that we had travelled very rapidly."

A banned substance

A few years later Sandoz filed a patent for LSD and marketed it as a treatment for anxiety disorders and for use in psychiatric research. While studies continued on its therapeutic effects, LSD rapidly gained popularity as a recreational drug among the American counterculture – first with the beat generation and later with hippies in search of freedom.

Views about the benefits and risks of LSD have fluctuated over the years, mainly in line with the prevailing drug policy. By the 1970s most countries, including Switzerland, had classified LSD as a narcotic and banned its sale, purchase and use, bringing an end to the research. To this day LSD remains a banned substance in Switzerland and practically all over the world.

Back in Swiss research labs

Albert Hofmann was against the use of LSD outside of a controlled environment, considering it too risky. But he always maintained it had its place as a means of exploring the human soul and coping with life's anxieties.

It was several decades before interest re-emerged in the potential of LSD for strictly medical purposes, and a new generation of clinical studies began. A small number of scientists are currently working in psychedelic research. One of them, Solothurn psychiatrist Peter Gasser, launched a study in 2007 on the benefits of LSD for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease. His primary intention, even before evaluating its therapeutic use, was to prove that LSD could be safely administered to patients in his therapy practice. Other recent studies, for example at the University of Basel, point to renewed interest in the medical potential of LSD. Matthias Liechti, who heads the psychopharmacology group at University Hospital Basel, is conducting research on the effects of LSD in healthy subjects and studying its effectiveness in the development of new drugs for mental disorders. In 2017 he participated in a study on the acute effects of LSD on the brain, finding that it reduces activity in the region of the brain related to the handling of negative emotions like fear.

As to the man who started it all, Albert Hofmann passed away in 2008 at the age of 102 – apparently none the worse for his psychedelic experiences. At an LSD symposium marking his centenary in Basel two years earlier, Hofmann told the crowd he last took LSD at the age of 97!

Translation based on an article by Pascaline Minet published in Le Temps in July 2017.

* LSD: My Problem Child [English translation], OUP Oxford, 2013.